An Island in Denial

I sleep uneasily tonight in Western Australia’s premier tourist destination where − unknown to most visitors − hundreds of terrified Aboriginal prisoners from every part of the state suffered and died in unimaginably brutal squalor.

I dream of lawyers and police, knowing from official WA Government archives that the thick limestone walls around my cramped hotel bedroom conceal a dark history of violent horror and abuse. A blocked second doorway and the faint mark of a former dividing wall reveal my premium twin-share unit (pictured on right) was once two cells, each 3m by 1.7m – less than the size of a small family car – and my adjoining bathroom a third cell. In each tiny cell slept seven prisoners, huddled shivering on the cold, damp limestone floor with no room to move, no toilet bucket, a tiny slit high in the rear wall to admit light and a windy gap under the cell door for air. I think of this as I try to sleep, wondering if their ghosts still inhabit this dreadful place.

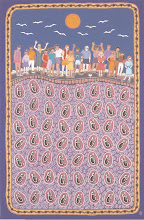

One in 10 prisoners who slept here died of disease, malnourishment or was bashed to death by prison guards. Others were flogged with lead-weighted whips or chained across a raised iron bar for punishment. Prisoners were lined up in the central courtyard and collapsed in shock when forced to watch five condemned men hanged, their bodies carted to a nearby dump and buried in unmarked graves. At least 370 Aboriginal prisoners are buried nearby, each wrapped in the filthy blanket in which they died and seated – according to custom – facing east to greet the rising sun over the land of their ancestors. I think of this too as I walk at dawn over the nation’s biggest unmarked burial ground, a neglected wasteland in Western Australia’s premier holiday resort − Rottnest Island.

One in 10 who slept here died of disease, malnutrition or was bashed to death by prison guards

From WA Government archives

Thousands of visitors flock to this Indian Ocean tourist paradise year-round. Luxury cruisers from Perth’s wealthy western suburbs jam its sheltered bays in summer and island visitor accommodation is costly and scarce, even in winter. A wild week on “Rotto” after final exams is an annual right of passage for thousands of West Australian “schoolies”. I first visited Rottnest with two Year 11 classmates in 1966. We camped with scores of others in Tentland, between The Settlement and The Basin – the island’s popular swimming hole. Tentland was still thriving in 1974 when I shared a nearby cottage with three other young adults. We rode bikes past the busy campsite to swim at The Basin, never imagining that just below where I slept as an innocent 15-year-old lay the bodies of hundreds of Aboriginal men who died in brutal captivity.

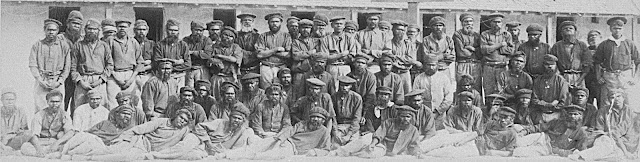

It was not until last May, on my third annual Rottnest winter holiday, that I discovered the full extent of this island’s shameful past. At the back of the island’s small museum are photographs of Rottnest’s early history as an Aboriginal prison. One shows two rows of prisoners (pictured) in front of their cells − including the one in which I now sleep. Their faces reflect grim despair. Aboriginal prison labour under extreme cruelty and miserable conditions built most of the island’s popular heritage landmarks, including Government House (now Rottnest’s biggest hotel), Hay Store (museum), Church, Salt Store, original waterfront cottages and The Quod – a notorious eight-sided jail in which at least 370 Aboriginal men died, their cells now occupied by laughing tourists oblivious to the past horror of their surroundings.

‘Aboriginal people don’t come here because

it’s a sad place for us’

it’s a sad place for us’

Wadjuk elder Noel Nannup, on

why many Aboriginal families

shun Rottnest Island

From there, I walk to the Salt Store, where a “Reconciliation Week” photographic display shows Aboriginal forced labour at the former saltworks and symbolic efforts to heal the past. When I ask volunteer guide Bob Chapman for more information about the prison, he disappears into a small office behind a partition and returns with a thick file of old papers in a battered manila folder. “It’s all in here,” he says, inviting me to sit and read a 30-year-old collection of photocopied reports, book extracts and typewritten manuscripts. As I turn the pages of the “Aboriginal Prisons File”, my two-week Rottnest idyll changes from relaxation to incredulity, and growing awareness of an island in denial.

It begins when I ask another volunteer guide in The Settlement why there are not more signs to inform visitors about the prison and what really happened. “Some people think there are too many heritage plaques already, so there aren’t any more,” she says. Later, I notice an Aboriginal man near the shops, and it strikes me that I don’t recall ever seeing an Aboriginal person on Rottnest before. It’s Wadjuk elder Noel Nannup from the island’s new Wadjemup bus tours that offer tourists a glimpse of local Aboriginal history, culture and connection to country.

“Aboriginal people don’t come here because it’s a sad place for us,’ he says quietly. “There are many Aboriginal men buried here from all over Western Australia. Our families remember what happened. We don’t dwell on the past but we don’t gloss over it.” He explains that Wadjemup is the Nyoongar name for Rottnest and means “land over the sea where the spirits of the dead go” – a place of powerful significance for many Aboriginal people. Salt Store records quote Perth elder Ken Colbung as saying Rottnest Prison was a double punishment for South-West Nyoongars because the “Island of Spirit People” was also a “Winnaitch” - a forbidden place.

“Aboriginal people don’t come here because it’s a sad place for us,’ he says quietly. “There are many Aboriginal men buried here from all over Western Australia. Our families remember what happened. We don’t dwell on the past but we don’t gloss over it.” He explains that Wadjemup is the Nyoongar name for Rottnest and means “land over the sea where the spirits of the dead go” – a place of powerful significance for many Aboriginal people. Salt Store records quote Perth elder Ken Colbung as saying Rottnest Prison was a double punishment for South-West Nyoongars because the “Island of Spirit People” was also a “Winnaitch” - a forbidden place.

Rottnest Prison was double punishment because the ‘Island of Spirit People’ across the water was also a ‘Winnaitch’ - a forbidden place

Perth elder Ken Colbung

The Wadjemup bus tour takes 90 minutes and traverses the island with stories about local plants, animals and sea creatures, and explains that Nyoongars lived here 7,000 years ago when Rottnest was part of the mainland. The tour’s motto is “No guilt, no blame” but passengers are invited to pause for a moment’s silence in a shady paperbark grove in the centre of the island to hear the wind sighing through the trees and reflect on the impact dark stone cells had on Aboriginal men who once roamed free under open skies. Noel Nannup says Aboriginal women on the mainland lit fires on the far shore for prisoners to see across the water and would “talk to the whales, asking them to bring their men home”. On our way back, the distinctive Wadjemup bus with a bright blue whale (pictured below right) painted on each side doesn’t go anywhere near the Aboriginal burial ground, which is my next stop.

The burial ground was strewn with empty bottles and cans, toilet paper, building rubble

and the rotting remains of a dead quokka

and the rotting remains of a dead quokka

Every visit is now a sad shock. On my first trip in May, a temporary hessian fence, a heritage plaque and a wooden sign bordered a sandy wasteland where the earliest graves are known to lie. The ground was littered with empty cans and bottles, scraps of building rubble, toilet paper and the rotting remains of a dead quokka – a small marsupial found everywhere on Rottnest Island. Holiday-makers rode bikes over a sandy track through the middle, disregarding a sign to “please respect this area”. In a wooded grove formerly occupied by Tentland, several trees were marked with white crosses. A half-full beer bottle lay on a log next to a discarded can of rum and cola.

Another temporary hessian fence round a nearby demolition site bore a WA Government notice that read: “The Aboriginal Burial Ground is Under Repair. Rottnest Island was a native prison from 1838 to 1931. Thousands of Aboriginal leaders and warriors were imprisoned on the island during this period and more than 370 remain in the Burial Ground in the largest unmarked Burial Ground in Australia. PLEASE RESPECT THIS SACRED PLACE AT ALL TIMES”. A detailed map showed landscaped gardens, an “entrance look-out and shelter”, a viewing terrace”, “sculptural sentinels” and “reflection spaces”.

Plans for Australia's "largest unmarked burial ground"

- but nothing has been done

- but nothing has been done

When I return five months later, the fences and wooden sign have gone and a new metal plaque erected - bigger but harder to read from afar - and island workers and visitors (pictured right) still use the sandy wasteland as a shortcut from The Settlement shops to nearby workers’ cottages and The Basin. The Aboriginal display at the Salt Store has also gone – it went when Reconciliation Week ended. The Settlement is now swarming with primary school children on organised excursions but when I buy another Wadjemup bus tour, I am the only passenger. My handwritten ticket is issued at the Visitor Centre by a young worker who marks it "aboliginal tour”.

‘It is quite probable the curse of drink, together with the supplanting of black children by mixed races, will eventually cause them to die out’

Book on sale to tourists in new Rottnest Island Museum shop

I gatecrash a small group of “heritage” guests on a WA Government tour to explain new plans for the island. The island’s post office and souvenir shop closed in June and part of the museum has been turned into a gift shop to “commercialise” operations. The manager of Rottnest’s monopoly bicycle hire shop is now also new manager of the Rottnest Island Museum Shop. She admits she’s never been on the Wadjemup tour, which is touted by the WA Government as a showpiece of local Aboriginal reconciliation. A Government official explains that the museum’s integrity is secure because every item sold will first be vetted by the Rottnest Island Authority.

On prominent display in the new shop is a 2007 reprint of a 1901 booklet by John G. Withnell: “The Customs and Traditions of the Australian Natives of North Western Australia”. It begins: “Most of the young men being in the employment of the whites prefer to imitate them, caring little or nothing for their elders’ teachings. So it is merely a matter of time when they become extinct. It is quite probable that the curse of drink, together with the supplanting of black children by mixed races, will eventually cause them to die out, for it is reasonable to suppose that few intellectual persons will find companionship in the natives, so they merely gain the evil part of the European element from those who do associate closely with them”. The shop is filled with curious Asian and European tourists, and parties of primary school children and teachers queue outside to enter. I buy Withnell’s book and stash it in my bag.

Up to 167 Aboriginal prisoners at a time were locked in The Quod’s 29 tiny cells

WA historians Neville Green

and Susan Moon

Most of the Government’s museum tour is occupied by detailed discussion of the building’s architecture and plans to link the museum to the nearby General Store, across a narrow laneway filled with rubbish bins and forklift pallets. Noel Nannup is there too and says: “We’d rather see the museum restored to its original state as a hay store and mill. Aboriginal prisoners built this place and worked in it. We feel entitled to have a say but I don’t know if anyone will listen.”

The tour is all about “interpretation”, ‘interaction”, “awareness” and “story telling” – the modern bureaucratic jargon of Aboriginal reconciliation. Earlier, at a “Cleansing and Welcome” ceremony on the beach in which everyone is invited to throw handfuls of sand into the water, a white woman turns to me and says: “It’s such a privilege to be here”. When I ask why, she points to a nearby pelican feeding in the shallows.

Many Aboriginal prisoners spoke no English or each others’ languages − ‘they would have been terrified’

Noel Nannup, on

Battye Library records

The tour group walks a short way to Lomas Cottage, just 20 paces from Australia’s biggest unmarked burial site. The cottage contains photographs of Aboriginal prisoners hunting with spears on a Sunday, when they received no prison rations and had to find their own food among the island’s wildlife. Two photographs show tall men from the north marked with initiation scars and white ochre painted on their arms, legs and torsos. Another shows a small group of Nyoongars in drab prison garb (pictured) slumped around a dismal campfire. “They look sad, don’t they,” says Noel Nannup sitting quietly in a corner of the small room, gazing up at his ancestors on the far wall. Nobody else seems to notice, and soon the group is off again for the Salt Store, then lunch and more plans at Kingston Barracks. Nobody notices the sandy wasteland to their right, where 370 Aboriginal men are buried and forgotten.

Government records in Western Australia’s Battye Library detail the appalling death rate and savage brutality meted out to many of the island’s 3,670 Aboriginal prisoners between 1841 and 1903. In “The grim years – 1855-1902” from their book "Far From Home - Aboriginal Prisoners of Rottnest Island 1838-1931", historians Neville Green and Susan Moon write that up to 167 prisoners at a time were jammed into the Quod’s 28 tiny cells. Government records show some prisoners were as young as eight years and others in their seventies. As white settlement spread outwards from the expanding Swan River Colony, Rottnest’s prison population swelled correspondingly. Aboriginal prisoners were often shackled by the neck and ankles in heavy iron chains and marched hundreds of kilometres overland for transfer to Rottnest Island. Men and boys from vastly different country with different languages, dialects and customs were all lumped together. Many spoke no English and could not speak each others’ languages. “They would have been terrified,” Noel Nannup says.

Prisoners lay cold and wet surrounded by excrement on damp stone floors as deadly influenza raged through their draughty cells

From State archives

Aboriginal men from as far as the Gascoyne, Fitzroy River and the Kimberley arrived up to 20 at a time, shivering in chains in an open boat, cold, wet and seasick, clad only in thin blankets. Many were tribal warriors and clan leaders who had borne the brunt of settlement frontier conflict and were often jailed for pay-back killings or stealing food when their traditional hunting lands were forcibly removed. They had no immunity to influenza, measles, mumps and whooping cough, all introduced diseases that decimated weakened men held in close confinement with no sanitation, proper food or dry clothing. Many suffered pneumonia, scurvy, eczema and dysentery as they lay wet and shivering in threadbare blankets on cold stone floors, constantly damp in winter from being flushed out daily with buckets of cold water to remove overnight faeces and urine. Government records show that carrots, parsnips mangel-wurzel, beetroot, turnips and potatoes from the Prison Superintendent’s garden were fed to horses and pigs, sold to warders or thrown away. Aboriginal prisoners got only bread, meat, rice, tea and sugar, except on Sundays when they got nothing.

Prisoners were forced to straddle an iron bar attached to a chain ‘making it impossible to lie down or even sit comfortably’

Report by visiting JPs, Battye Library

The stench from the jail’s open cesspit was so nauseating that Chief Warder Adam Oliver complained to an 1884 Government inquiry headed by Surveyor-General (later Premier) John Forrest that the “offensive air” was permeating his quarters and ruining the health of his wife and four children. In winter, prisoners lay cold and wet surrounded by excrement on damp stone floors as deadly influenza raged through their draughty cells. Oliver told the inquiry there was no truth to newspaper reports that pigs were raking up the bodies of dead prisoners, although Master Carpenter John Watson said he had seen pigs in the cemetery. The Chief Warder also said he believed the treatment of prisoners was “humane and kind, with the exception of the deficiency of clothing during the winter”. I think of this as I try to sleep in one of their cells.

The prison’s first and worst prison superintendent was a man now widely revered on Rottnest Island. Henry Vincent was a British veteran of the Napoleonic Wars and lost an eye in the Battle of Waterloo. West Australian journalist and author Trea Wiltshire describes Vincent in “Gone to Rottnest” as arriving in the colony with a reputation as “a severe disciplinarian”. Official records show he was barely literate. No records were kept for cause of death of the first 203 prisoners to die on Rottnest Island. Being separated from the mainland by a perilous journey in an open long boat gave Vincent licence to do much as he pleased. He punished prisoners with the cat o’ nine tails without authority and was ordered after a surprise visit by mainland JPs to cease restraining “troublesome prisoners” by forcing them to straddle an iron bar attached to a chain “making it impossible to lie down or even sit comfortably”.

Vincent killed and buried two Aboriginal prisoners without anyone’s knowledge, and tore the ear off another with his fingers

Sworn evidence to official inquiry

In evidence to an inquiry ordered in 1846 by colonial Governor John Hutt, British soldier Samuel Mottram reportedly claimed on oath to have been told by overseer Joseph Morris that Vincent killed and buried two Aboriginal prisoners without anyone’s knowledge. Private John Williams swore on oath that he saw part of an Aboriginal prisoner’s ear on the ground. Private Thomas Longworth said he saw Vincent “pull the ear rather severely, and then shaking his fingers, as if to throw something away off his hands, wipe his fingers on his trousers”. Later, he saw the prisoner “with the gristly part of one ear wanting”.

“Two men were beaten to death here,” says Noel Nannup as the Wadjemup bus tour passes a limestone quarry used to build The Settlement. Later, as we walk past the island’s popular bakery, he pauses by an old Moreton Bay fig tree (pictured above right) and says: “An old man was beaten to death just here,” pointing to the spot. “I can feel it.” It’s hard to know if this is true because there are no official records for the cause of death of hundreds of Aboriginal prisoners who died here. But it is impossible to dispute my tour guide’s claim that “Vincent was a brute, he was a shocking man”.

A sick 60-year-old Aboriginal prisoner on his knees was bashed twice in the face with iron keys, kicked unconscious on the floor and died

From State archives

In one recorded incident in 1865, a sick 60-year-old Aboriginal prisoner was bashed twice in the face with a bunch of iron keys while on his knees for refusing to leave his cell. He rolled to the floor, was kicked unconscious and died that night in his cell. A post-mortem found the prisoner died of “lung disease” but Henry Vincent’s son, William – who was Assistant Superintendent – was convicted of assault and sentenced to three months’ hard labour in the Police stables before later getting a job as a police officer. Most islanders, including Rottnest Island Pilot Captain (later Island Superintendent) William Jackson, reportedly believed Henry Vincent killed the elderly Aboriginal prisoner and that William took the blame to shield his father.

Despite his record of callous brutality, Henry Vincent is venerated as an island pioneer and builder on many of The Settlement’s heritage plaques. Vincent’s name takes pride of place over a big fireplace in the popular Governor’s Bar on an annual Henry Vincent golf trophy with a brass inscription that honours him for building The Settlement. Rottnest Island’s official website invites visitors “to learn about the island’s rich cultural history” by walking the “Vincent Way Heritage Trail”.

‘Some even picked up skulls and ran away with them’

Official report on bodies

unearthed in 1962

But Australia’s biggest unmarked burial ground remains unrecognised and neglected. I walk back from Lomas House with a Government officer who says money is the problem. The island is expected to pay for itself but many see heritage protection as a state-wide issue, particularly when it comes to healing the wounds inflicted on Aboriginal people imprisoned here from every part of the state. The Government’s official response appears to be much talk but little action.

Sewerage works to extend the golf course in 1970 unearthed 12 skeletons in a grove of pine trees near the Quod. Island Manager Des Sullivan reported to the Rottnest Island Board on 19 June 1970 that the sewer was raised about 1.5m to clear the top of the bodies and the discovery hushed up “as this might have encouraged vandals to desecrate the graves”. In a 1979 interview, Mr Sullivan said he felt there might be hundreds more bodies in the area. However, it was not until 1985 that the State Government’s Aboriginal Sites Department formally recorded the burial ground and its rough location. After a big protest meeting on Rottnest in 1988, the Government conducted a ground-penetrating radar survey to establish the likely extent of the burial ground but Aboriginal representatives objected to test holes being dug to confirm the results.

The sewer was raised 1.5m to clear the top of the bodies

and the discovery hushed up

and the discovery hushed up

1970, when more bodies were unearthed

In 1992, the State Aboriginal Affairs Planning Authority budgeted $400,000 to help build a commemorative centre and memorial near the burial ground. The State Advisory Council of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Council (ATSIC) was asked to contribute another $400,000 and help fund annual costs of $200,000 for staff and maintenance. ATSIC refused and the project lapsed. In June 1994, WA Premier Richard Court acknowledged to another state-wide gathering of Aboriginal representatives on Rottnest Island that the site was the largest death-in-custody burial ground in Western Australia. However, nothing was done.

Neville Green speculates that “very few societies in the world would convert to tourist accommodation prison cells in which an estimated 287 people died in miserable conditions thousands of kilometres from their homelands and families. It is comparable to transforming (Nazi Germany’s) Auschwitz concentration camp into holiday cottages. Tourists and well as the general public should be made aware of the fact that many men died in the holiday units of the Quod.”

‘It is comparable to transforming Auschwitz concentration camp

into holiday cottages’

into holiday cottages’

Historian Neville Green on The Quod

A guest information folder in my former prison cell says “Henry Vincent built the octagonal shaped quod in 1838. Authorities were worried because Indigenous Australians in captivity back on the Mainland were fretting and dying and thought Rottnest might be a good alternative. Each cell contained up to 5-7 prisoners at one time”. No mention that each twin-share unit was actually three cells holding a total of 21 men who slept on a damp, cold stone floor with no toilet, that five men were hanged in the courtyard and at least 370 prisoners died from disease and beatings.

The Rottnest Island Authority’s 2008-09 annual report shows $450,000 earmarked for “Aboriginal reconciliation and economic development” over the next five years with funding from the “RIA budget and external sources”. In a 128-page Management Plan 2009-2014 subtitled “Revitalised and Moving Forward”, Western Australia’s Minister for Tourism, Liz Constable, says “The Island must pay for itself. Western Australian holidays cannot be subsidised by the Government.” Page 45 shows the same burial ground map that disappeared with the hessian fence next to the site. Page 46 says: “Repair and interpretation of the Aboriginal Burial Ground is a major project which is seen as a high priority reconciliation initiative of international significance and an economic driver for tourism.” And finally, in small print in brackets at the end of “Part 5 Aboriginal Reconciliation” under “Initiative 8 – Aboriginal reconciliation and economic opportunities for Aboriginal people” comes the punch-line: “Burial Ground interpretation requires external funding”. More jargon, obfuscation, buck-passing and inaction.

‘Authorities were worried because Indigenous Australians in captivity back on the Mainland were fretting and dying and thought Rottnest might be a good alternative’

Quod accommodation guest information

I email questions to the Rottnest Island Authority but staff are distracted by the tragic death the previous day of a child crushed when a brick pillar collapsed on a hammock at an island holiday cottage. There are public calls for all similar rental accommodation to close for safety fears on the eve of schoolies week, one of the busiest times of the year for island traders. Journalists, photographers and TV crews descend on Rottnest to interview and photograph grieving relatives and friends, police, ambulance officers, island officials and anyone else they can grab for interview while a media helicopter hovers over the accident scene. Noel Nannup is sympathetic too but points out that a similar tragedy in which an Aboriginal child was electrocuted three weeks earlier while playing in a Government house with no safety wiring attracted only fleeting public interest. “That’s the way it always is for Aboriginal people,” he says.

‘The island must pay for itself’

WA Tourism Minister Liz Constable

In his 1937 memoir “Rottnest – Its Tragedy And Its Glory”, Edward Jack (Ned) Watson writes: “Tonight I stood in the moonlight with my two boys at the foot of a large cypress tree that marks the spot where the body of Wanjibiddi was buried. With almost clairvoyant vision I could again see the large circle of cobblestone wall enclosing the graveyard; I could see all around me the familiar faces of Mangrove, Chillibabong, Matchikee and others. They are still sitting there wrapped in grey blankets with their faces towards the rising sun. In this attitude they were placed by their comrades who buried them over fifty years ago. About 70 skeletons are buried where the camper now pitches his tent or lights his outdoor fire. They are only four feet below the sand.”

Before I return to the mainland just a half-hour ferry ride away, I pay one last visit to Australia’s biggest unmarked burial ground and gaze with the morning sun behind me across the sandy tract scuffed by bicycle tyre tracks and footprints. I see two rows of Aboriginal men staring grimly from the prison photograph and wonder how many of them might now be looking back at me from their sandy graves just below the ground.

Later, as sea spray whips my face on the bumpy ferry ride back to Fremantle, I think about the ironic injustice of Henry Vincent’s legacy and the fact that despite nearly 50 years of government research, reports, meetings and promises, at least 370 Aboriginal prisoners still lie largely forgotten in unmarked graves in the middle of the state’s most popular holiday destination. And I think of Wadjuk elder Noel Nannup in his empty Wadjemup bus, fighting a lone battle each day to win recognition and respect for his forgotten ancestors. Nothing much, it seems, has changed in 171 years.

© 2009 Michael Sinclair-Jones except for “Welcome to Rottnest” by Sally Morgan (permission granted for use) and prisoner photographs courtesy State Library of Western Australia (Battye Library 20982P & 694B/2). Quod drawing based on PWD Plan 149 traced in 1928 from 1876 sketch by Richard Jewell.

.jpg)